Sin Of Fibbing Examples

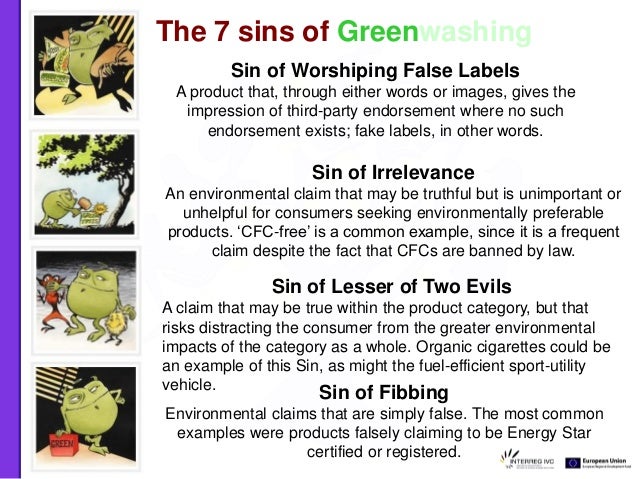

The Sin of the Hidden Tradeoff: The green version of the “glittering generality,” this sin involves presenting a product as green by highlighting a single environmental attribute (only focusing, for instance, on recycled content, or a manufacturer’s efforts to lower carbon emissions, without looking at the full range of environmental impact).2. The Sin of No Proof: As the name suggests, this sin refers to making environmental claims that have no evidence to back them up.3. The Sin of Vagueness: This sin involves feel-good language that’s so vague as to be meaningless. For instance, ever seen something labeled “chemical-free?” The report points out that this can’t be true: everything contains chemicals — water’s a chemical. A product may be free of specific toxic chemicals, but, of course, the claim doesn’t say that.4. The Sin of Irrelevance: Making a claim that’s truthful but unimportant or unhelpful.

For example, saying cigarettes are organic. #7 Sin of Fibbing. Environmental claims that are blatantly false. For example, saying that a diesel car emits zero carbon dioxide Carbon Credit A carbon credit is a tradable permit or certificate that provides the holder of the credit the right to emit one ton of carbon dioxide or an equivalent of in the air. Jan 17, 2012 - Common examples are tissue products that claim various. Sin of fibbing. The least frequent Sin is committeed by making environmental.

Any product currently labeled “CFC-free,” for instance, engages in this form of greenwash, because all products are currently CFC-free: these compounds have been banned for nearly twenty years.5. The Sin of Lesser of Two Evils: Are cigarettes “green?” What about “eco-friendly” pesticides and herbicides? Labeling such products “green(er)” ultimately distracts from the fundamental problems with these products.6. The Sin of Fibbing: This really doesn’t require much of an explanation.

The Sin of Fibbing: This really doesn’t require much of an explanation. Terrachoice noted that this was the least prevalent form of greenwashing it encountered in its survey, but there were a few products bearing claims that were simply untrue.

Terrachoice noted that this was the least prevalent form of greenwashing it encountered in its survey, but there were a few products bearing claims that were simply untrue.7. The Sin of Exaggerating: An example is the Statoil commercial for Bio95, which is a fuel with 5% bioethanol and 95% gasoline, presenting the car turning into a green grass field when you fill it up. The environmental impact from this fuel is in best case equal to the pure gasoline.

Lying, as defined by, is a statement at variance with the mind. This definition is more accurate than most others which are current. Thus a recent authority defines a lie as a statement made with the intention of deceiving. But it is possible to lie without making a statement and without any intention of deceiving. For if a man makes a statement which he thinks is, but which in reality is he certainly lies inasmuch as he intends to say what is, and although a well-known liar may have no intention of deceiving others for he knows that no one believes a word he says yet if he speaks at variance with his mind he does not cease to lie.Following and, divines and writers commonly make a distinction between (1) injurious, or hurtful, (2) officious, and (3) jocose lies. Jocose lies are told for the purpose of affording amusement. Of course what is said merely and obviously in joke cannot be a lie: in order to have any malice in it, what is said must be naturally capable of deceiving others and must be said with the intention of saying what is.

An officious, or white, lie is such that it does nobody any injury: it is a lie of excuse, or a lie told to benefit somebody. An injurious lie is one which does harm.It has always been admitted that the question of lying creates great difficulties for the moralist. From the dawn of speculation there have been two different opinions on the question as to whether lying is ever permissible., in his Ethics, seems to hold that it is never allowable to tell a lie, while, in his Republic, is more accommodating; he allows and statesmen to lie occasionally for the good of their patients and for the common weal.

Modern are divided in the same way. Allowed a lie under no circumstance.Paulsen and most modern non-Catholic writers admit the lawfulness of the lie of necessity. Indeed the pragmatic tendency of the day, which denies that there is such a thing as absolute, and measures the morality of actions by their effect on and on the individual, would seem to open wide the gates to all but injurious lies. But even on the ground of pragmatism it is well for us to bear in mind that white lies are apt to prepare the way for others of a darker hue.There is some difference of opinion among the. Quotes and approves of his on this point (Stromata, VI). He says that a man who is under the necessity of lying should diligently consider the matter so as not to exceed. He should gulp the lie as a sick man does his medicine.

He should be guided by the example of Judith, Esther, and Jacob. If he exceed, he will be judged the enemy of Him who said, 'I am the Truth.' Held that it is lawful to deceive others for their benefit, and Cassian taught that we may sometimes lie as we take medicine, driven to it by sheer necessity., however, took the opposite side, and wrote two short treatises to prove that it is never lawful to tell a lie. His on this point has generally been followed in the, and it has been defended as the common opinion by the and by modern divines.It rests in the first place on.

In places almost innumerable seems to condemn lying as absolutely and unreservedly as it condemns and fornication. Gives expression in one of his to this interpretation, when he says that forbids us to lie even to save a man's life. If, then, we allow the lie of necessity, there seems to be no reason from the point of view for not allowing occasional and fornication when these crimes would procure great temporal advantage; the absolute character of the moral law will be undermined, it will be reduced to a matter of mere expediency.The chief argument from reason which and other have used to prove their is drawn from the nature of.

Lying is opposed to the virtue of. Truth consists in a correspondence between the thing signified and the signification of it.

Man has the power as a reasonable and social being of manifesting his thoughts to his fellow-men. Right order demands that in doing this he should be truthful. If the external manifestation is at variance with the inward thought, the result is a want of right order, a monstrosity in nature, a machine which is out of gear, whose parts do not work together harmoniously.As we are dealing with something which belongs to the moral order and with virtue, the want of right order, which is of the essence of a lie, has a special moral turpitude of its own. There is precisely the same malice in, and in this vice we see the moral turpitude more clearly. A pretends to have a good quality which he knows that he does not possess. There is the same want of correspondence between the mind and the external expression of it that constitutes the essence of a lie.

The turpitude and malice of are obvious to everybody.If it is more difficult to realize the malice of a lie, the partial reason, at least, may be because we are more familiar with it. Truth is primarily a self-regarding virtue: it is something which man owes to his own rational nature, and no one who has any regard for his own dignity and self-respect will be guilty of the turpitude of a lie. As the is justly detested and despised, so should the liar be. As no honest man would consent to play the, so no honest man will ever be guilty of a lie.The absolute malice of lying is also shown from the consequences which it has for. These are evident enough in lies which injuriously affect the and reputations of others.

But mutual confidence, intercourse, and friendship, which are of such great importance for, suffer much even from officious and jocose lying. In this, as in other moral questions, in order to see clearly the moral quality of an action we must consider what the effect would be if the action in question were regarded as perfectly right and were commonly practiced. Applying this test, we can see what mistrust, suspicion, and utter want of confidence in others would be the result of promiscuous lying, even in those cases where positive injury is not inflicted.Moreover, when a habit of untruthfulness has been contracted, it is practically impossible to restrict its vagaries to matters which are harmless: interest and habit alike inevitably lead to the violation of to the detriment of others. And so it would seem that, although injury to others was excluded from officious and jocose lies by definition, yet in the concrete there is no sort of lie which is not injurious to somebody.But if the common teaching of on this point be admitted, and we grant that lying is always wrong, it follows that we are never justified in telling a lie, for we may not do that good may come: the end does not justify the means. What means, then, have we for protecting secrets and defending ourselves from the impertinent prying of the inquisitive? What are we to say when a dying man asks a question, and we that telling him the will kill him outright?

We must say something, if his life is to be preserved: he would at once detect the meaning of silence on our part. The great difficulty of the question of lying consists in finding a satisfactory answer to such questions as these.held that the naked must be told whatever the consequences may be. He directs that in difficult cases silence should be observed if possible. If silence would be equivalent to giving a sick man unwelcome news that would kill him, it is better, he says, that the body of the sick man should perish rather than the of the liar. Besides this one, he puts another case which became classical in the.

If a man is hid in your house, and his life is sought by murderers, and they come and ask you whether he is in the house, you may say that you where he is, but will not tell: you may not deny that he is there. The, while accepting the teaching of on the absolute and intrinsic malice of a lie, modified his teaching on the point which we are discussing. It is interesting to read what St. Wrote on the subject in his Summa, published before the middle of the thirteenth century. He says that most agree with, but others say that one should tell a lie in such cases. Then he gives his own opinion, speaking with hesitation and under correction. The owner of the house where the man lies concealed, on being asked whether he is there, should as far as possible say nothing.

If silence would be equivalent to betrayal of the secret, then he should turn the question aside by asking another How should I? or something of that sort. Raymund, he may make use of an expression with a double meaning, an equivocation such as: Non est hic, id est, Non comedit hic or something like that. An number of examples induced him to permit such equivocations, he says.

Jacob, Esau, Abraham, Jehu, and the made use of them. Or, he adds, you may say simply that the owner of the house ought to deny that the man is there, and, if his tells him that this is the proper answer to give, then he will not go against his, and so he will not. Nor is this direction contrary to what Augustine teaches, for if he gives that answer he will not lie, for he will not speak against his mind ( Summa, lib. I, De Mendacio).The gloss on the chapter, 'Ne quis' (causa xxii, q.2) of the Decretum of Gratian, which reproduces the common teaching of the at the time, adopts the opinion of St.

Raymund, with the added reason that it is allowable to deceive an enemy. Lest the should be unduly extended to cases which it does not apply, the gloss warns the student that a witness who is bound to speak the naked may not use equivocation. When the of equivocation had once been introduced into the it was difficult to keep it within proper bounds. It had been introduced in order to furnish a way of escape from serious difficulties for those who held that it was never allowed to tell a lie.

The and other secrets had to be preserved, this was a means of fulfilling those without telling a lie. Some, However, unduly stretched this.

They taught that a man did not tell a lie who denied that he had done something which in he had done, if he meant that he had not done it in some other way, or at some other time, than he had done it. A servant, for example, who had broken a window in his master's house, on being asked by his master whether he had broken it, might without lying assert that he had not done so, if he meant thereby that he had not broken it last year or with a hatchet.

It has been reckoned that as many as fifty authors taught this, and among them were some of the greatest weight, whose works are classical. There were of course many others who rejected such equivocations, and who taught that they were nothing but lies as indeed they are. The German, Laymann, Who died in the year 1625, was of this number. He refuted the arguments on which the was based and conclusively the contrary. His adversaries asserted that such a statement is not a lie, inasmuch as it was not at variance with the mind of the speaker.

Laymann saw no force in this argument; the man that he had broken the window, and nevertheless he said he had not done it; there was an evident contradiction between his assertion and his thought. The words used meant that he has not done it; there were no external circumstances of any sort, no use or custom which permitted of their being understood in any but the obvious sense.

They could only be understood in that obvious sense, and that was their only meaning. As it was at variance with the of the speaker, the statement was a lie. Laymann explains that he did not wish to reject all.Sometimes a statement receives a special meaning from use and custom, or from the special circumstances in which a man is placed, or from the mere fact that he holds a position of trust. When a man bids the servant say that he is not at home, common use enables any man of sense to interpret the phrase correctly.

When a pleads 'Not guilty' in a court of, all concerned understand what is meant. When a statesman, or a doctor, or a lawyer is asked impertinent questions about what he cannot make known without a breach of trust, he simply says, 'I don't know', and the assertion is, it receives the special meaning from the position of the speaker: 'I have no communicable on the point.' The same is of anybody who has secrets to keep, and who is unwarrantably questioned about them. Prudent men only speak about what they should speak about, and what they say should be understood with that reservation. Writers call statements like the foregoing, and they qualify them as wide in order to distinguish them from strict.

These latter are equivocations whose sense is determined solely by the mind of the speaker, and by no external circumstances or common usage. They were condemned as lies by the on 2 March, 1679. Since that time they have been rejected as unlawful by all writers.

It should be observed that when a wide reservation is employed the simple is told, there is no statement at variance with the mind. For not merely the words actually used in a statement must be considered, when we desire to understand its meaning, and to get at the mind of the speaker. Circumstances of place, time, and manner form a part of the statement and external expression of the thought. The words, 'I am not guilty', derive the special meaning which they have in the mouth of a on his trial from the circumstances in which he is placed.

It is a statement of fact whether in reality he be guilty or not. This must be understood of all restrictions which are lawful.

The virtue of requires that, unless there is some special reason to the contrary, one who speaks to another should speak frankly and openly, in such a way that he will be understood by the addressed. It is not lawful to use without good reason. According to the common teaching of and other divines, the hurtful lie is a mortal, but merely officious and jocose lies are of their own nature venial.The which has been expounded above reproduces the common and universally accepted teaching of the throughout the until recent times.

From the middle of the eighteenth century onwards a few discordant voices have been heard from time to time. Some of these, as Van der Velden and a few French and writers, while admitting in general a lie is intrinsically wrong, yet argued that there are exceptions to the rule. As it is lawful to kill another in, so in it is lawful to tell a lie. Others wished to change the received definition of a lie. A recent writer in series, Science et Religion, wishes to add to the common definition some such words as 'made to one who has the to.'

So that a statement knowingly made to one who has not a to the will not be a lie. This, however, seems to ignore the malice which a lie has in itself, like, and to derive it solely from the social consequence of lying. Most of these writers who attack the common opinion show that they have very imperfectly grasped its meaning.

At any rate they have made little or no impression on the common teaching of the. About this pageAPA citation. In The Catholic Encyclopedia.

Name That Sin

New York: Robert Appleton Company. Slater, Thomas. The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910.Transcription. This article was transcribed for New Advent by Sara-Ann Colleen Hill.Ecclesiastical approbation.

Nihil Obstat. October 1, 1910.

Remy Lafort, Censor. Farley, Archbishop of New York.Contact information. The editor of New Advent is Kevin Knight.

My email address is webmaster at newadvent.org. Regrettably, I can't reply to every letter, but I greatly appreciate your feedback — especially notifications about typographical errors and inappropriate ads.